“Global Learning” often conjures up images of students’ on-site explorations in “foreign” spaces through summer travel or full semesters abroad. Certainly such learning pathways can be productive ones. But my participation in TCU’s Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) of Discovering Global Citizenship has helped me see that some of the most powerful opportunities for facilitating global learning occur through our campus-anchored classrooms. In this, my final report as a Koehler fellow, therefore, I want to shine a spotlight on the work several colleagues have been doing to center their courses in intercultural experiences. This survey of practices will focus on ways of bringing others’ expertise into our classrooms while encouraging students to step outside their cultural comfort zones through research and experiential learning.

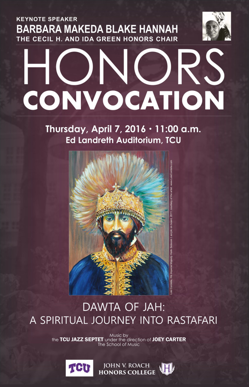

Darren Middleton’s spring semester offering of “Rastafari and Reggae in Global Contexts” provides a compelling example of his commitment to globalized teaching. One component of the class involved visitors from Jamaica: Barbara Makeda Blake Hannah, a filmmaker, journalist, and broadcaster, and her musician son Makonnen Blake Hannah. Darren secured support for the Hannahs’ visit from both the QEP Visiting Scholars program and the Honors College Green Chair, which enabled Barbara to serve as this year’s Honors Convocation speaker.

Barbara’s convocation talk drew rave reviews, but the students in Darren’s class had a more intensive chance to interact with her. Notes Darren:

Barbara’s convocation talk drew rave reviews, but the students in Darren’s class had a more intensive chance to interact with her. Notes Darren:

students were able to put a face … on one of the twenty-first century’s most vibrant, durable and globalized new religious movements. Students discovered that while it is one thing to read about Rastafari from a book and/or to listen to reggae on Spotify, it is quite another thing to engage as well as encounter its revolutionary ethos (spiritually, politically, culturally) in the flesh.

The impact of this in-person connection carried over into end-of-course projects, which enabled class members to learn by doing and sharing their own research. As Darren recalls,

Students . . . finished their semester with five sessions devoted to “Global Reggae Projects,” where each group of three students researched and outlined (for the class as a whole) how reggae music has traveled the world (UK, Canada, Senegal, Japan, Brazil) and been translated into local words and sounds, which articulate the specific spiritualities and particular politics of fresh cultural contexts.

Research has also played a key role in globally-oriented courses taught by 2015-16 Honors Teacher of the Year Juan Carlos Sola-Corbacho. His students are encouraged to hone their researching skills as a way of building knowledge about cultures beyond the US. Reflecting on his lower- division offering of an Honors “Cultural Contact Zones” class, Juan Carlos describes how the syllabus took class members on cross-cultural journeys through scaffolded research experiences:

This semester [spring 2016] we took a very long trip in “only” 16 weeks. . . .We began in Belize, where we learnt not only about its history, political system, social structure or difficult economic situation, but also about the famous Belize Carnival, or the Great Blue Hole (largest underwater sinkhole in the world)…. The rest of the semester we continued our trip learning about wonderful places we need to preserve (Galapagos Island in Ecuador or Machu Piccu in Peru), historical characters we need to remember (Fidel Castro, Eva Peron or Alejaidinho), amazing traditions (Fiesta Nacional de Zapote -Costa Rica-, Dia de la Tradición -Argentina-) or even good recipes to try at home such as “green fig and salt fish” (national dish of Saint Lucia) or “anafres” (traditional Honduran appetizer).

Juan Carlos also devoted a good deal of energy to developing a partnership course for fall 2016—one that will connect students at TCU with peers at the University of Debrecen (in Debrecen, Hungary) and tap into one of the recurring strategies that TCU’s QEP initiative has promoted: creating “virtual voyages.”

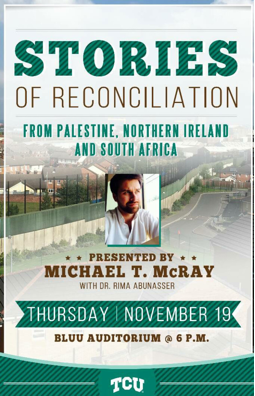

Networking with the QEP’s Discovering Global Citizenship programming also brought global learning dividends to teaching by Rima Abunasser. Invited by QEP committee member James English to link up with a special initiative involving journalist Michael McRay’s study of international reconciliation projects, Rima connected an Honors section of her Global Women’s Literature course to his travels to sites of longstanding cross-cultural conflict that have been working to develop strategies for supporting reconciliation. Rima carefully crafted a syllabus that would allow her students to go along virtually on McRay’s activist research journey that, she reports, included his interviewing of “peacemakers, activists, former combatants, and politicians in three locations — Northern Ireland, Palestine, and South Africa.” For maximum learning impact, Rima explains:

I modified my existing reading list to include literature from each of the regions he would visit, and I did extensive research on transitional justice and reconciliation….I requested that [Michael] also film some B-roll footage (walking around, scenery, crowd shots, etc.) and designed the students’ major assignment around the ideas of narrative building and perspective. In small groups, the students were required to edit and produce short documentaries of Michael’s travels. The goal of this assignment was to illustrate how, even with the same raw material, each group would come up with its own narrative, its own perspective on justice, conflict, and reconciliation. Michael was able to Skype in to our classes a few times during the semester.

In November, McRay visited the TCU campus, joining Rima’s students in documentary editing workshops and classroom conversations. Two of the student documentaries were screened in a public event that provided a capstone for the course.

In November, McRay visited the TCU campus, joining Rima’s students in documentary editing workshops and classroom conversations. Two of the student documentaries were screened in a public event that provided a capstone for the course.

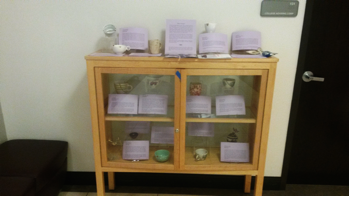

While the idea of cross-cultural networking tends to connote a voyage out, College of Education professor Amber Esping encouraged students to look inward through a capstone project for her pilot Honors colloquium on “Resilience.” Blending a commitment to metacognition with an exploration of cross-cultural aesthetics, Amber’s students each spent part of class time for three weeks creating art work grounded in the Japanese practice of Kintsugi. This “art of broken pieces” is an ancient method of using powder and strong resin to repair pottery. Amber explains:

In the resulting piece, the damage is not hidden. Rather, the damage is illuminated, honoring the history of the object. Using the urushi resins makes the repaired areas stronger—and arguably more beautiful—than the original undamaged object. This is an ancient, tangible metaphor for the concepts of resilience the students have been learning about throughout the semester, serving as an enduring keepsake to remind them of their own and others’ capacity for resilience.

Kintsugi is a painstaking process popular in Japan, but in United States culture we are more liable to throw out a broken dish, or if we do fix it we want the repair to be fast and invisible. Below, see Amber’s students’ public display of their art works:

Learning about yourself by interacting with others from a different cultural background was also a major theme of Hanan Hammad’s spring 2016 Honors course. Her class addressed the same general learning outcomes as Sola- Corbacho’s course on the Americas, but her course content focused on a different region—one tied to her research in Middle Eastern studies and her own personal identity. Professor Hammad moved students from studying the history and politics behind current conflicts in Syria and Iraq to interaction with local immigrants from those regions in Fort Worth. Working in pairs, students were assigned to a family who had agreed to serve as mentors for cross-cultural learning; meeting with refugees in their homes, Hanan’s students also made themselves available to assist with some of the complex challenges faced by newcomers, such as navigating public school expectations for immigrant children. In presentations of their learning during the final week of the class, students emphasized a shift in their own identities and socio-historical awareness through their exploration of global issues in a local context.

Significantly, when asked to offer advice to other faculty members who might be open to “globalizing” their teaching, Professor Middleton issued an invitation that could have been based directly on the content of his colleague Professor Hammad’s course:

Besides underlining the importance of crafting syllabi that stimulate mental migration to different parts of our world, I would say this: The D/FW Metroplex is one of the most culturally diverse areas in our nation, which entails that the world is on our doorstep. Dare to be creative. Think of the many communities beyond the classroom. And then find fresh ways to connect experiential learning to the many resources that live and move around us.

In Darren’s call, set in the context of the rich array of pedagogical initiatives described throughout this report, we can trace the outlines of a shared vision for intercultural education. While each of these talented teacher-scholars embraced a unique approach for promoting global learning, they also drew on a shared aspiration for global learning consistent with TCU’s core values, vision. As the Honors College and the larger university travel forth into new arenas of action represented by exciting endeavors like the new medical school, let’s all still continue to affirm the value of this equally important dimension of our work as educators for the twenty-first century.

This article was written by Sarah Robbins, Department of English and 2016 Koehler Center Fellow for Global Citizenship, with contributing authors: Rima Abunasser, Amber Esping, Hanan Hammad, Darren Middleton, and Juan Carlos Sola-Corbacho for the Fall 2016 Issue of Insights.